Image: Martis Wildlife Area, taken by Michelle Prestowitz at TRWC

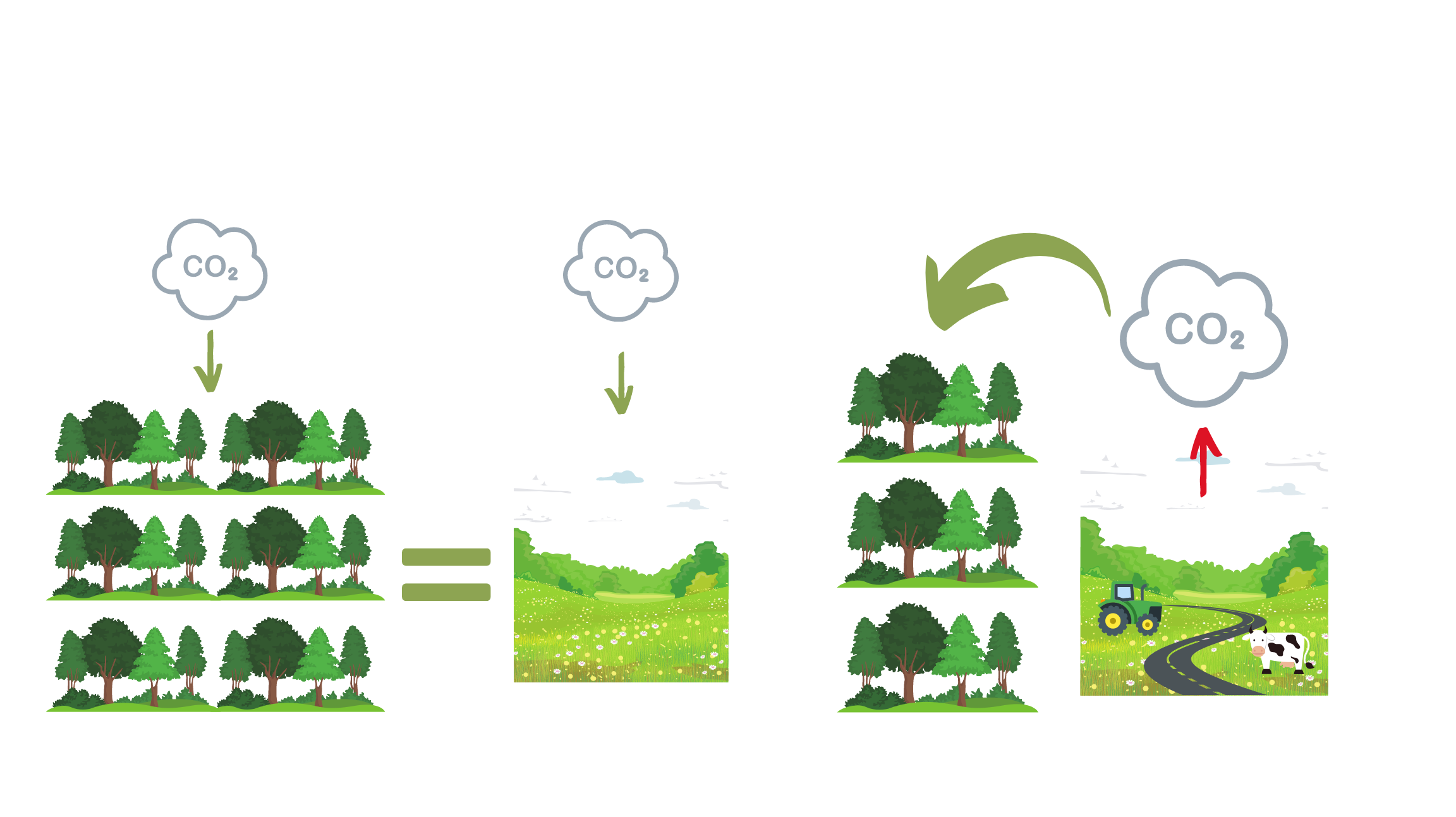

Typically we think of forests as the lungs of the Earth, sucking up excesses of carbon dioxide and gifting us back clean oxygen. Many climate change mitigation projects highlight reforestation as an avenue through which we can enhance Earth’s ability to draw carbon down and store it in forests where it can’t heat our planet. And while forests do certainly play an important role in carbon drawdown and sequestration, there is another critical carbon sink that warrants more of our attention: meadows.

Soils store three times more carbon than vegetation (including trees) and the atmosphere combined. And meadows are among the largest naturally known occurring terrestrial carbon sinks. But only, recent research suggests, if they are healthy.

A couple of weeks ago, the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency presented preliminary results for their Tahoe Basin Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory. Included were findings from their survey of meadows around the Tahoe Basin. Prior to development around the Basin, there were around 6,608 acres of meadows, marshes and fens; today, 40% of those have either been lost to development or are in degraded condition.

The TRPA reported that while pristine meadows act as carbon sinks, absorbing a net of +30,000 mtCO2e/year, degraded meadows actually emit carbon at a net magnitude of -20,000 mtCO2e/year. According to another 2020 study, one acre of healthy Sierra meadow can sequester as much carbon as six acres of surrounding forest. On the other hand, three acres of forest are required to offset the amount of carbon lost by one acre of degraded meadow. The bad news is that across the Sierra Nevada, 50% of meadows are expected or known to be degraded. These findings should have massive implications for our climate mitigation and land management priorities here in the Sierra and across our planet.

“One acre of healthy meadow can sequester as much carbon as six acres of forest. On the other hand, three acres of forest are required to offset the amount of carbon lost by one acre of degraded meadow”

The Sierra Nevada contains over 18,000 meadows; though these account for only 2% of the area’s land cover, they are thought to contain roughly ⅓ of the landscape’s soil organic carbon. And unlike forests, which store their carbon in wood above-ground, meadows largely store carbon below-ground amongst their dense root systems. This makes them less susceptible to disturbances like wildfire that cause forests to release their stored carbon into the atmosphere.

Healthy meadows are not just carbon sinks – they also add resilience to the hydrologic and ecological processes that sustain California’s headwaters. In the spring, meadows absorb snowpack meltwater, storing it and slowly releasing it over time. They improve downstream water quality by filtering out sediment and pollutants, and ultimately provide some 60 percent of California’s developed water supply. Their dense root systems resist erosion and during the summer, montane meadows are considered the single most important bird habitat in the Sierra Nevada.

Both anthropogenic and climate impacts cause meadow degradation, but humans have acted as the primary stressor. Over the last century, meadows in the Sierra have been inundated by reservoirs, destroyed by livestock grazing, and drained for agriculture, development, roads, and logging. These activities channelize meadows, compact soils, erode streams and deplete native plants and animals communities, diminishing meadows’ abilities to sequester carbon and perform other critical ecosystem services.

McIver Dairy Meadow in Truckee offers a local example of the sorts of restoration efforts that are so critical. Formerly used as a dairy operation, the meadow was found by Truckee River Watershed Council (TRWC) to be releasing two tons of polluted sediment annually into the Truckee River. Though carbon measurements were not taken, its highly degraded state almost certainly meant that it was operating as a carbon source. In a collaborative effort, the Town and TRWC restored the meadow by removing fill, reconnecting the local creek to its meadow floodplain, and reintroducing native plants. This restoration effort improves carbon sequestration potential, increases the quality of the water running into the Truckee River, and provides more habitat for native plants, birds, and wildlife. Due to the recent restoration efforts, sledding at McIver has been relocated away from the sensitive site to allow for rehabilitation.

Other research and restoration efforts in the area are ongoing – The Sierra Meadows Partnership, a group of government, university, and non-profit partners, has been researching and restoring Sierra Nevada meadows formally since 2016, and informally since 2010. The Town has several other sites for which it has also planned or completed restoration projects. These and other efforts are critical to growing the resilience of our land and our communities.

There is no silver bullet to climate change. We need a diverse suite of strategies and widespread collaboration to achieve our GHG reduction goals and support thriving communities. Meadow restoration is perhaps small in the scheme of things, but maintaining these carbon-sequestering meadows is one tool to add to our climate action toolkit – and every tool matters.

By: Sara Sherburne, CivicSpark Fellow